ke.. ![]() sekarang kita membahas cara mengganti Logo Rock Legends tanpa Street Cred..

sekarang kita membahas cara mengganti Logo Rock Legends tanpa Street Cred..

Yg perlu kamu lakukan ..

- Download Add-Ons Di sini

- Setelah itu kmu Instal, dan Restart Firefox nya..

- Cari gambar yg akan di jadikan logo ( GIF, JPG, PNG, dll )

- Copy Link gambar tersebut, ( ato simpen dulu di Notepad )

- Login Facebook

- Buka App Rock Legends nya

- Click Home ato Your Band, lalu edit

- Dan keluar gambar seperti ini

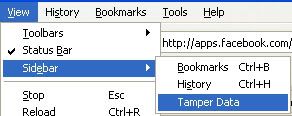

- Lalu Click Toolbar Firefox View > Sidebar > Tamper Data

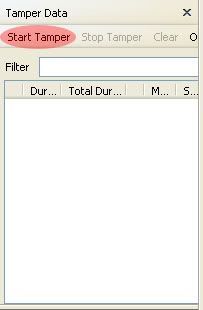

- Click STAR TAMPER

- Pada Edit Your Band langsung Click Save Changes Terus Click Tamper

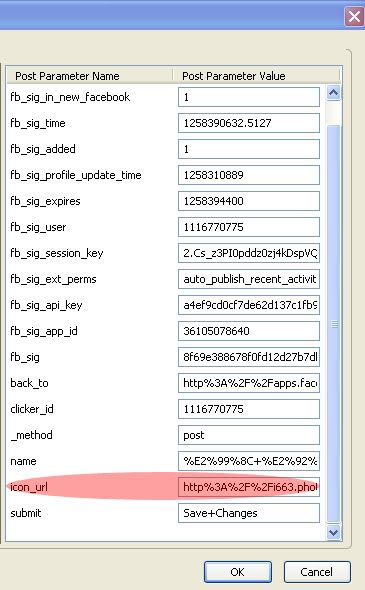

- Lihat pada gambar kanan

- Lalu paste Link Gambar yg udah kmu siapin tadi di icon_url, lalu Click OK dan STOP TEMPER. Tunggu Loading selesai dan lht Band kmu..

- Lalu...

::Skips shooting Program::

1. Warm up

2. Stretch

3. Shoot 100 shots from anywhere on the court.

4. Make 15 right hand lay ups

5. Make 15 left hand lay ups

6. Make 15 right hand finger rolls

7. Make 15 left hand finger rolls

8. Make 15 reverse lay ups with right hand

9. Make 15 left hand reverse lay ups

10. Shoot 15 free throws

11. Water break-5 minutes

12. Form shooting inside five feet (concentrate on perfect form and not hitting the rim.)-30 shots.

13. Form shooting between 5 and 15 feet. (Concentrate on perfect form and not hitting rim.)-35 shots.

14. Spin pass into your shot from anywhere on the court-35 shots

15. Spin pass into your shot from each baseline inside 3-point arc. (Spin pass from block, catch the ball, pivot and shoot, get rebound and repeat from other side.)-35 shots.

16. Spin pass into your shot from right wing to left wing-30 shots

17. Spin pass into your shot from the key area-30 shots

18. Spin pass into your shot with one-shot fake and a dribble-30 shots

19. Shoot free throws-15 shots

20. Water break-5 minutes

21. Jump shot with dribble- 30 shots

22. Jump shot with a special move (i.e. crossover, spin move, etc..)-20 shots

23. Speed dribble into jump shot-10 shots

24. Change of pace-10 shots

25. Stutter-10 shots

26. Inside out-10 shots

27. Crossover-10 shots

28. Shoot 15 free throws

29. Water break-5 minutes

30. Creative Shots-20 shots

30. 3-pointers-35 shots

31. Beat the Rival- to 10 points

32. Shoot 100 jumpers, rcord your score and try to beat it every day.

33. Shoot 100 free throws, record your score and try to beat it every day.

Bag the Groceries

1. Put the ball in your shirt

2. Hit it out

Leg Lift

1. Dribble behind your back

2. Now bend one leg back and dribble under the shin of that leg

3. Keep doing this swicthing legs

Ball Wrap

1. With the ball in your right, bring it over to the left a bit

2. Now put your left hand on the right side of the ball

3. Now lightly toss the ball over your left hand and move your right hand back to catch it

Step Over

1. With the ball in your right, dribble it around your back so it will come out on the left side, make sure the dribble is real low

2. Now when the ball comes out, step over the ball with your right leg by bringing it accross and stepping on the left side of the ball

3. Now pick it up

Blaze Twist (by Johny Blaze from the notic)

1. With the ball in your right, bring it to the right side

2. Now bring it up by your left shoulder and swing it a lil bit behind your head but keep your arm in front fo your face

3. Once the ball gets to the right sholder drop it

4. Now spin on the left going counter clock wise

5. Grab the ball with your right

Blaze Back Twist (by Johny Blaze from the notic)

1. With the ball in your right, bring it over to the left a bit and at the same time jump a 360 counter clockwise

2. When your back is towards where you were facing before (like the imaginary D) lift your leg up (either one) and put the ball under it to the left hand

3. Land the spin facing fowards again and the ball should be in

Fire Blaze (by Johny Blaze from the notic)

1. With the ball in your right, bring it to the right side

2. Now bring it up by your left shoulder and swing it a lil bit behind your head but keep your arm in front fo your face

3. Once the ball gets to the right sholder drop it

4. Now spin on the left going counter clock wise

5. Grab the ball with your right

Banna Split (by Goosebumps from the notic)

1. Lift your left leg up and with the ball in your right put it under it and throw it up a lil bit behind your back

2. Now move over to the left so the ball will be behind your back and at the same time catch the ball with your right hand by reaching it bakc

3. Once u catch it let it bounce once on the right

4. Turn around clockwise and grab the ball with your left

Goosebumps (by Goosebumps from the notic)

1. With the ball in your left, toss it out to the left a bit

2. Now with your right, reach over and grab the ball by the top and cup it

3. Bring it bakc while and then put it behind your back to the left while spinning in the direction that it brings you

Dream Weaver (by Hope Dreams from the notic)

1. With the ball in your right, bring it under your left arm and behind you and throw it up back to your right side

2. Now with your left reach under your right arm and catch the ball

3. Now throw it back up to the left side and wit your right, bring it under your left arm and catch it

4. Etc.

Dream Roll (by Hope Dreams from the notic)

1. Sit on the ball

2. Now put your right hand down on the ground and roll away from the ball towards the left and at the same time start to roll over onto your stomach while on the ball

3. So the stomach went from under your butt to now under your stomach, now just flip off

Kick Off (by Hope Dreams from the notic)

1. Toss the ball towards your feet

2. Now kick it right back to you

Dragon Breath (by Goosebumps from the notic)

1. Do the dragon walk (found in the hot sauce moves page)

2. Now once you step over the ball with a foot, make a half turn so you are facing the opposite direction as you were when u started

3. Now continue doing the dragon walk but backwards

Dragon Claws (by Dazid Dazzle from the notic)

1. Roll the ball on the ground

2. Now with your right foot, bring it over to the left side and move it forward and around the ball back to the right side

3. Now do the same thing with your left foot but bring it to the right side and around back to the left

4. Keep doing it for as long as you like

HOW TO MAKE FREESTYLEZ

Freestylez are almost something natural. It's just showing off. Dribbling around. It's best if you have your own style of freestyling. Here are some tips to help you make some up

+ dribble in different positions

+ dribbling in and out of your leg

+ throwing the ball up and doing something

+ rolling on the ground

+ and whatever else you can think of

Hurricane

(Optional) Cross through your legz to your opposite hand

(Optional) Catch it with the other hand with your arms stretched out making your body an X

1. Bring the ball to the opposite side (where the ball originally started) and throw it under that leg back to the same hand

Flinstone Shuffle

1. With the ball in your right start driving left and throw the ball on his left side so he dosen’t see it

2. When you throw the ball flick your wrist down giving it a little backspin, keep driving so he will keep guarding you

3. After about 3 steps of driving shuffle back to his left side (your right and get the ball)

4. He should stumble back to keep up with you

Dragon/kat walk

1. Let the ball roll/bounce on the ground

2. Your right foot and step over the ball to the left side of it

3. Now take your left foot and bring it over the ball to the right side, etc

4. Keep doing it until you reach near the D

5. Now stop doing the walk and tap the ball through his legs and go around and get it

Hypnotizer

1. Get the D low and reaching for the ball

2. Bring the ball behind your back with one hand and throw it over both of your heads so it will land behind him. Do this with one hand and make sure he dosen’t see you do it

3. Fake dribble a little bit to confuse him and go around and get the ball

Jacknife

1. Get the D low

2. Bring the ball around his head and hold it behind it with both hands

3. Now throw it up towards the left and a little bit backwards

4. Now run forward to the right like if you have the ball and driving

5. Stop and come back and get the ball while he stumbles back onto D

Backstabber

1. Get the D low

2. Bring the ball around him and nail it on his shoulder blade

3. Hold it there and he won’t be able to reach it

4. When you feel like it take it off and get the ball

IF HE TURNS AROUND

5. Turn with him

6. This way he can’t get the ball even if he tries to turn around to get it

Ice

1. Get the D’s legz open

2. Bring the ball to the opposite side you have it in right now and throw it through his legs

3. Go around on the side you did the move and get the ball

Boomerang

1. Get the D low

2. Once he is bring the ball behind him, reach kinda far out

3. Now give it a flick so it will come back to you

4. Stand back and catch it

5. He should turn around, now you can throw it off his back or butt and get it again

Sauce 2k/Air Shamgod

1. Toss the ball up with one hand

2. Now before it reaches below your waits bring the opposite arm over and catch it under the ball bring it back to the side that u caught it

UFO

1. With the ball in your right, bring it over to the right side of the D's head (your left)

2. Now bring it behind his head just a lil bit and throw it up

3. Now quickly throw it up and drive to the left

4. step back and get the ball while he stumbles back on D

Slo mo cross

1. Ring the ball down like you are about to dribble through your legs reall slow

2. Suddenly when you are about to dribble speed up

Stiff leg cross

1. Your cross between your legs a couple of times

2. Pretend your gonna do it again but bring the ball and hold it on the side of your inner thigh while you bring your arm under like you crossed. try flinging the arm that you are not doing the move to like u just got the cross

3. They should move to the direction u "crosses" and just take the ball and go pass them on the other side.

Pick-up

1. Roll the ball around on the ground

2. Now slap the ball near the front having it to snap into your wrist

3. Now just kinda reach under the ball and pick it up, this is done extremely fast

Ball on head

1. Get the D low

2. Bring the ball and put it on his head

3. Roll it off back to you

Boomatwist

1. Get close to the hoop

2. Throw the ball at the board spin to the direction you kinda threw yourself into (example if I threw the ball with right I would spin left)

3. Once u finish the spin the ball should bounce off and come back to you

4. Catch it and the D should be confused

Hands up

1. Bring the ball up with your palm on the bottom

2. When it's about to hit his face kinda swing the ball upside down so ur hand is ontop

3. The D should just jump bak or put their hands up

phantom

1. Put your shirt over your face.head and play normally

Callin u out

1. Play with a cell phone

Phantom

1. Play with your shirt over your head

Twister/Tornado

1. Get the D low

2. Bring the ball over their head and continue spinning towards that direction bringin the ball with you

3. Once u finish the spin he should turn around

Twister II/Tornado II

1. Do the twister/tornado

2. This time once u finish the spin put the ball in your shirt

3. Then hit it out

Reflector

1. Do the Sauce2k except when you catch it, catch it on the outer side of the ball like your hitting/reflecting it back to you

Back Paddle

1. Do inside out dribbles behind your back like faking your gonna put it thru your legs from back to front, do this a couple of times

2. Now cross behind your back and blow pass him or roll it thru both your legs and go get it

U-Turn

1. With the ball in your right, go right like you are driving

2. Now bring the ball over to your left side and bounce it back where u came from and at the same time turn the opposite way back to where you started

Butter Roll

1. Slam the ball on the ground

2. Roll it a little bit and then do the pickup

3. Right after you pick it up slam it down again, do the pickup, slam it down, etc

1. jaga jarak.

2. kuda-kuda defense diperkuat kalo gak kamu bisa jatuh.

3. no look eyes, jangan pernah melihat mata, karena mata bisa menghipnotis, seperti pesulap yang bisa menghipnotis hanya dengan mempengaruhi matanya

4. low defense, posisi badan saat defense lebih merendah seperti dribling

5. no steal, jangan coba2 untuk steal, bisa-bisa kamu kena ankle breaker

6. gerakan tangan siap mengantisipasi trick.

7. baca kelemahan lawan, tangan mana yang menurut kamu lemah dalam driblingnya,atau kekurangan lawan apa, kalo di gak punya shooting bagus ngapain menempel ketatnya.

mungkin ini bisa bermanfaat, jangan mau kena trick lawan!

Spot the difference

Can birds raised in complete isolation evolve “normal” species song over generations?

Cold Spring Harbor, NY – During infancy, each of us emerges from a delightful but largely incoherent babble of syllables and learns to speak – normally, in the language of those who care for us. But imagine what would happen if we were somehow raised in utter isolation from other people, not only our parents but also from surrogates such as nurses and nannies. What sort of culture might we evolve if reared in isolation? Would we learn to speak? Would such a language evolve over multiple generations? If so, would it eventually resemble existing ones?Such an experiment is not practical to conduct in humans, but an analog has been performed among a species of songbirds called zebra finches. The study, which will appear online ahead of print on May 3rd in the journal Nature, provides new insights into how genetic background, learning abilities and environmental variation might influence how birds evolve "song culture" —and provides some pointers to how languages may evolve.

The study confirms that zebra finches raised in complete isolation do not sing the same song as they would if raised normally, i.e., among other members of their species. It breaks new ground in showing that progeny of these "odd birds," within several generations, will introduce improvisations that bring their song into conformity with those of "wild-type" zebra finches, i.e., those raised under normal cultural conditions. The study is the product of a collaboration between Professor Partha Mitra and Haibin Wang of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) and Olga Feher, Sigal Saar and Ofer Tchernichovski at City College New York (CCNY).

Bringing culture into the laboratory

Young zebra finches learn to sing by imitating adult male songbirds. But when raised in isolation, the young sing a raspy, arrhythmic song that's different from the song heard in the wild. To find out what happens to this "isolate song" over generations, the scientists designed experiments in which these isolated singers passed on their song to their progeny, which in turn tutored the next generation, and so on. The tutors were either paired one-on-one with their progeny, or to mimic a more natural social setting, introduced into a colony of females (who, as it happens, do not sing) and allowed to breed for a few generations.

The team found that in either social setting, birds of every successive generation imitated their tutor's song but also modified it with small, systematic variations. These improvisations weren't random, however. Accumulating over generations, the introduced changes began to bring the innate, "isolate" song into approximate conformity with the song learned within normal zebra finch "society." (This "cultured" song has been labeled "wild-type" by the scientists.) By the 4th or 5th generation, birds that were descendents of the experimental "isolates" were singing songs that very closely resembled the song sung by birds raised under social conditions in the wild.

"What is remarkable about this result is that even though we started out with an isolated bird that had never heard the wild-type, cultured song, that's what we ended up with after generations," explains Mitra. "So in a sense, the cultured song was already there in the genome of the bird. It just took multiple generations for it to be shaped and come about."

"People have theorized long and hard about how the evolutionary process applies to culture," he says. "This experiment takes culture and puts it into a laboratory setting. We've tested some questions, asked by others over many years, in a mathematically and experimentally crisp manner and come up with a concrete answer."

Model motivations

What the results also mean, according to Mitra, is that the cultured song that's heard in the wild is the product of genes and learning – a combination of innate song that would be learned even in isolation, and the effects of a learning process iterated over multiple generations. This insight was initially a hypothesis that Mitra developed to address a conundrum familiar to scientists studying songbirds.

Scientists have known for decades that the "innate" song of an isolated songbird is different from the "learned" song of a songbird that was tutored by an adult. But where did that adult tutor's song come from? Obviously from it's own father, but where did this passed-down song originate? "This is a classic chicken-and-egg problem," says Mitra.

He hypothesized that if the song of an isolated songbird were transmitted over multiple generations, the normal wild-type song would somehow spontaneously emerge. Using what mathematicians call a "recursive equation," he came up with a mathematical model of how this might happen. This model, combining ideas from the literature on cultural evolution and quantitative genetics, tries to quantify the relative contributions of the songbird's genetic background, learning ability and environmental factors to the emergence of the cultured song.

Multigenerational progress towards song culture

To experimentally test his hypothesis, Mitra five years ago approached his long-time collaborator, Professor Ofer Tchernichovski, Ph.D., a songbird biologist at CCNY. Tchernichovski and his graduate student Olga Feher took up the experimental challenge, raising songbirds in soundproof boxes and collecting audio and video recordings of their subjects. Mitra and CSHL postdoctoral fellow Haibin Wang in turn analyzed these recordings, comprising a large dataset of several terabytes, which show that the innate song of an isolated bird is gradually transformed over multiple generations into a song that closely resembled the song normally found in the wild.

"I was more pleased than surprised with the experimental data," admits Mitra. "I came in with a strong bias that wild-type song culture would spontaneously emerge." His colleagues, the experimentalists, were careful to design the study to rule out potential artifacts. "There were all manner of environmental factors – the presence of the females, for instance – that could have changed the outcome and resulted in the emergence of a completely new song culture," Mitra says.

This work, the scientists maintain, now provides a unified experimental framework for researchers studying topics as diverse as cultural evolution, neuroethology (biology of song development) and quantitative genetics. "We've provided a starting point to explore the biology of cultural transmission in the laboratory," says Mitra. Read More..

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- For decades, a debate has simmered in the educational community over the best way to teach children how to read. Proponents of phonics, the "whole language and meaning" approach and other teaching methods long have battled for dominance, each insisting that theirs is the superior strategy.

Now, a Florida State University researcher has entered the fray with a paper in the prestigious journal Science that says there is no one "best" method for teaching children to read.

Carol M. Connor is an assistant professor in the FSU College of Education and a researcher with the Florida Center for Reading Research. Along with colleagues from FSU and the University of Michigan, she wrote "Algorithm-Guided Individualized Reading Instruction," published in Science’s Jan. 26 issue. (The magazine is available online to subscribers at www.sciencemag.org.) Connor’s paper shows that lots of individualized instruction, combined with the use of diagnostic tools that help teachers match each child with the amounts and types of reading instruction that are most effective for him or her, is vastly preferable to the standard "one size fits all" approach to reading education that is prevalent in many American elementary schools.

"There is too much of a tendency in education to go with what ‘sounds’ really good," Connor said of various educational trends that come into and fall out of fashion. "What we haven’t done very well is conduct comprehensive field trials and perform the rigorous research that are the norm in other fields of science. With this study, we sought to do just that — to take a systematic approach to what works, what doesn’t, and why" when teaching students to read.

The researchers found that "the efficacy of any particular instructional practice may depend on the skill level of the student. Instructional strategies that help one student may be ineffective when applied to another student with different skills." The trick, then, is to more precisely determine the reading skill level of each child and then find a way to cater the curriculum to each student’s individual needs.

"Instead of viewing the class as an organism, we’re trying to get teachers to view the students as individuals," Connor said.

While that may sound daunting to the typical first- or second-grade teacher, Connor has turned to technology to offer a helping hand. She, Frederick J. Morrison and Barry Fishman, professors at the University of Michigan, have developed "Assessment to Instruction," or A2i, a Web-based software program. A2i uses students’ vocabulary and reading scores and their desired reading outcome (i.e. their grade level by the end of first grade) to create algorithms that compute the recommended amounts and types of reading instruction for each child in the classroom. The software then groups students based on learning goals and allows teachers to regularly monitor their progress and make changes to individual curricula as needed.

A2i currently is being tested by about 60 elementary-school teachers in one Florida county. However, "right now A2i is just a research tool," Connor said. "Hopefully we’ll be able to make it available more widely as time goes on."

Chronic reading problems and depression appear to be related, especially among low-income children, and the reading problems precede the depression.

A new study done by researchers at the University of Delaware and West Chester University of Pennsylvania found that low-income children who take part in reading assistance programs in fifth grade are more depressed, anxious, and withdrawn than their peers, especially when they have chronic reading problems. The study is reported in the March-April 2007 issue of the journal Child Development.

Children from low-income families often have difficulties in reading and math achievement in early elementary school, and these problems increase as they rise in grade level. This study sought to determine if and when reading difficulties are associated with emotional distress.

The researchers looked at 105 4- to 12-year-old children who took part in a longitudinal study of the emotional development of disadvantaged children. Mothers and teachers provided information about reading assistance when the children were in the third and fifth grades, achievement scores documented reading difficulty, teachers rated problem behaviors in school that reflect emotional distress, and the children reported about their own recent negative emotional experiences, including sadness, shame, and fear. The study took into consideration children’s verbal abilities and family income.

Researchers found that fifth grade reading problems were associated with increases in emotional distress from third to fifth grade. Children in reading assistance programs in fifth grade showed more distressed behaviors than those in third grade, whether or not they were in reading programs at that time. And children who were in reading programs in both third and fifth grades were the most distressed.

These children also reported especially high levels of negative emotional experiences. The results tie the emotional distress to developmental changes in children’s understanding of academic ability between 9 and 12 years of age.

“Much research documents the common academic difficulties of economically disadvantaged children,” according to Brian P. Ackerman, professor of psychology at the University of Delaware and lead author of the study. “Little is known, however, about the emotional impact of these difficulties and participation in remediation programs, or whether the impact changes with age.

“Our results suggest that such difficulties have special emotional significance for preadolescent children, but perhaps not for younger children, and that attending to the emotional impact could help prevent school disengagement for disadvantaged children.”

West Lafayette, IN – July 9, 2008 – Researchers led by Steven R. Wilson of Purdue University videotaped forty mothers as they completed a ten minute play period with one of their children between the ages of three and eight years. The mothers then completed a series of questionnaires including the Verbal Aggressiveness Scale.

Mothers who scored higher on the self-reported VA Scale engaged in more frequent directing of their child's behavior during the play activities. These mothers were more likely to control activity choices as well as the pace and duration of activities. High VA mothers did so repeatedly and in a manner that tended to enforce an activity choice they had made. Low VA mothers were more likely to follow their child's lead or seek their child's input about choice of activity.

High VA mothers used physical negative touch (PNT) when trying to change their child's actions. Examples of parental PNT by high VA mothers included restraining a child by the shoulder or the wrist to prevent him or her from reaching a toy. No instances of PNT occurred for low VA mothers.

In addition, children with low VA mothers displayed virtually no resistance to their mother's directives. Children with high trait VA mothers occasionally resisted their mothers' directives, though this resistance tended to be indirect and short-lived.

"Our study has implications for parenting classes and interventions," the authors conclude. "In addition to talking about why it is important for parents to avoid lots of verbally aggressive behavior to avoid damaging their child's self-esteem, parents who have this tendency also need to learn how to follow their child's lead and read their child's signals, as opposed to just taking over the play period themselves."

Two studies that appear in the August/October 2005 issue of Current Anthropology challenge established linguistic theories regarding the language families of Amazonia.

New research by Dan Everett (University of Manchester) into the language of the Pirahã people of Amazonas, Brazil disputes two prominent linguistic ideas regarding grammar and translation. The Pirahã are intelligent, highly skilled hunters and fishers who speak a language remarkable for the complexity of its verb and sound systems. Yet, the Pirahã language and culture has several features that not known to exist in any other in the world and lacks features that have been assumed to be found in all human groups. The language does not have color words or grammatical devices for putting phrases inside other phrases. They do not have fiction or creation myths, and they have a lack of numbers and counting. Despite 200 years of contact, they have steadfastly refused to learn Portuguese or any other outside language. The unifying feature behind all of these characteristics is a cultural restriction against talking about things that extend beyond personal experience. This restriction counters claims of linguists, such as Noam Chomsky, that grammar is genetically driven system with universal features. Despite the absence of these allegedly universal features, the Pirahã communicate effectively with one another and coordinate simple tasks. Moreover, Pirahã suggests that it is not always possible to translate from one language to another.

In addition, Alf Hornborg's (Lund University) research into the Arawak language family counters the common interpretation that the geographical distribution of languages in Amazonia reflects the past migrations of the inhabitants. At the time of Christopher Columbus, the Arawak language family ranged from Cuba to Bolivia. Yet, geneticists have been unable to find significant correlations between genes and languages in the Amazonia. Moreover, Arawakan languages spoken in different areas show more similarities to their non-Arawakan neighbors than to each other, suggesting that they may derive from an early trade language. As well, Arawak languages are distributed along major rivers and coastlines that served as trade routes, and Arawak societies were dedicated to trade and intermarriage with other groups. But, the dispersed network of Arawak-speaking societies may have caused ethnic wedges between other, more consolidated language families with which they would have engaged in trade and warfare. Finally, there is increased evidence that language shifts were common occurrences among the peoples of Amazonia and were used as a way to signal a change in identity, particularly when entering into alliances, rather than migratory movement.

While communication may be recognized as a universal phenomenon, differences between languages -- ranging from word-order to semantics -- undoubtedly remain as they help to define culture and develop language. Yet, little is understood about similarities and differences in languages around the world and how they affect communication. Recently, however, two studies have emerged that aid in our understanding of cross-linguistic distinctions in language usage.

In a study examining the contrast in cross-cultural languages, known as cross-linguistics, researchers from CNRS and Université de Provence, and Harvard and Trento Universities found direct evidence to support word-order constraints during language production. Specifically, the way in which participants pronounced a set of words was dependent upon the preceding word as it varied across languages.

Psychologists Niels Janssen, F. Xavier Alario and Alfonso Caramazza presented French- and English-speaking individuals with colored objects and noted that, when the sounds were compatible, participants found color easier to pronounce than object names. For example, the object ‘rake’ in English was easier to pronounce when it was colored red than when it was colored blue, a finding that only held true for English speakers.

For French speakers, ‘râteau,’ meaning ‘rake,’ was as easy to pronounce in red as in blue, suggesting that the object-before-color syntax in French played a large part in language production.

These findings, which appear in the March 2008 issue of Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, provide insight into how word-order affects language production: “No matter how complex our thoughts, when we express them in speech, we produce them one by one,” explained Janssen. “And, the order in which these words should be uttered follows tight linguistic rules in many languages. As a result, each word is affected by its predecessor.”

However, language use is not only constrained by word-order but by meaning as well. In collaboration with researchers Mutsumi Imai, Eef Ameel, Naoaki Tsuda and Asifa Majid from universities in Japan, Belgium and The Netherlands, psychologists Barbara C. Malt from Lehigh University and Silvia Gennari from the University of York investigated whether participants speaking various languages identified two different words to distinguish between the acts of walking and running.

English-, Japanese-, Spanish- and Dutch-speaking individuals watched video clips of a student moving on a treadmill at different slopes and speeds. According to past research, English and Dutch verbs tend to express manner of motion, and Spanish and Japanese verbs tend to express direction of motion; these variations assure that any shared patterns in naming could not be attributed to structural similarities.

Despite the vast differences between the four languages, however, all participants used distinct words to describe when the student was walking and to identify precisely when she began running. These results, which also appear in the March 2008 issue of Psychological Science, indicate cross-linguistic commonalities in naming patterns for locomotion and help to support the notion of certain universal rules and constraints in all languages.

“We found that converging naming patterns reflect structure in the world, not only acts of construction by observers,” Malt stated. “On a broader level, the data reveal a shared aspect of human experience that is present across cultures and reflected in every language.”

Fundamental concepts

Lexemes and word forms

The term "word" is ambiguous in common usage. To take up again the example of dog vs. dogs, there is one sense in which these two are the same "word" (they are both nouns that refer to the same kind of animal, differing only in number), and another sense in which they are different words (they can't generally be used in the same sentences without altering other words to fit; for example, the verbs is and are in The dog is happy and The dogs are happy).The distinction between these two senses of "word" is arguably the most important one in morphology. The first sense of "word," the one in which dog and dogs are "the same word," is called lexeme. The second sense is called word-form. We thus say that dog and dogs are different forms of the same lexeme. Dog and dog-catcher, on the other hand, are different lexemes; for example, they refer to two different kinds of entities. The form of a word that is chosen conventionally to represent the canonical form of a word is called a lemma, or citation form.

Inflection vs. word-formation

Given the notion of a lexeme, it is possible to distinguish two kinds of morphological rules. Some morphological rules relate different forms of the same lexeme; while other rules relate two different lexemes. Rules of the first kind are called inflectional rules, while those of the second kind are called word-formation. The English plural, as illustrated by dog and dogs, is an inflectional rule; compounds like dog-catcher or dishwasher provide an example of a word-formation rule. Informally, word-formation rules form "new words" (that is, new lexemes), while inflection rules yield variant forms of the "same" word (lexeme).There is a further distinction between two kinds of word-formation: derivation and compounding. Compounding is a process of word-formation that involves combining complete word-forms into a single compound form; dog-catcher is therefore a compound, because both dog and catcher are complete word-forms in their own right before the compounding process was applied, and are subsequently treated as one form. Derivation involves affixing bound (non-independent) forms to existing lexemes, whereby the addition of the affix derives a new lexeme. One example of derivation is clear in this case: the word independent is derived from the word dependent by prefixing it with the derivational prefix in-, while dependent itself is derived from the verb depend.

The distinction between inflection and word-formation is not at all clear-cut. There are many examples where linguists fail to agree whether a given rule is inflection or word-formation. The next section will attempt to clarify this distinction.

Paradigms and morphosyntax

A paradigm is the complete set of related word-forms associated with a given lexeme. The familiar examples of paradigms are the conjugations of verbs, and the declensions of nouns. Accordingly, the word-forms of a lexeme may be arranged conveniently into tables, by classifying them according to shared inflectional categories such as tense, aspect, mood, number, gender or case. For example, the personal pronouns in English can be organized into tables, using the categories of person, number, gender and case.The inflectional categories used to group word-forms into paradigms cannot be chosen arbitrarily; they must be categories that are relevant to stating the syntactic rules of the language. For example, person and number are categories that can be used to define paradigms in English, because English has grammatical agreement rules that require the verb in a sentence to appear in an inflectional form that matches the person and number of the subject. In other words, the syntactic rules of English care about the difference between dog and dogs, because the choice between these two forms determines which form of the verb is to be used. In contrast, however, no syntactic rule of English cares about the difference between dog and dog-catcher, or dependent and independent. The first two are just nouns, and the second two just adjectives, and they generally behave like any other noun or adjective behaves.

An important difference between inflection and word-formation is that inflected word-forms of lexemes are organized into paradigms, which are defined by the requirements of syntactic rules, whereas the rules of word-formation are not restricted by any corresponding requirements of syntax. Inflection is therefore said to be relevant to syntax, and word-formation not so. The part of morphology that covers the relationship between syntax and morphology is called morphosyntax, and it concerns itself with inflection and paradigms, but not with word-formation or compounding.

Allomorphy and morphophonology

In the exposition above, morphological rules are described as analogies between word-forms: dog is to dogs as cat is to cats, and as dish is to dishes. In this case, the analogy applies both to the form of the words and to their meaning: in each pair, the first word means "one of X", while the second "two or more of X", and the difference is always the plural form -s affixed to the second word, signaling the key distinction between singular and plural entities.One of the largest sources of complexity in morphology is that this one-to-one correspondence between meaning and form scarcely applies to every case in the language. In English, we have word form pairs like ox/oxen, goose/geese, and sheep/sheep, where the difference between the singular and the plural is signaled in a way that departs from the regular pattern, or is not signaled at all. Even cases considered "regular", with the final -s, are not so simple; the -s in dogs is not pronounced the same way as the -s in cats, and in a plural like dishes, an "extra" vowel appears before the -s. These cases, where the same distinction is effected by alternative changes to the form of a word, are called allomorphy.

There are several kinds of allomorphy. One is pure allomorphy, where the allomorphs are just arbitrary. Other, more extreme cases of allomorphy are called suppletion, where two forms related by a morphological rule cannot be explained as being related on a phonological basis: for example, the past of go is went, which is a suppletive form.

On the other hand, other kinds of allomorphy are due to the interaction between morphology and phonology. Phonological rules constrain which sounds can appear next to each other in a language, and morphological rules, when applied blindly, would often violate phonological rules, by resulting in sound sequences that are prohibited in the language in question. For example, to form the plural of dish by simply appending an -s to the end of the word would result in the form *[dɪʃs], which is not permitted by the phonotactics of English. In order to "rescue" the word, a vowel sound is inserted between the root and the plural marker, and [dɪʃəz] results. Similar rules apply to the pronunciation of the -s in dogs and cats: it depends on the quality (voiced vs. unvoiced) of the final preceding phoneme.

The study of allomorphy that results from the interaction of morphology and phonology is called morphophonology. Many morphophonological rules fall under the category of sandhi.

Lexical morphology

Lexical morphology is the branch of morphology that deals with the lexicon, which, morphologically conceived, is the collection of lexemes in a language. As such, it concerns itself primarily with word-formation: derivation and compounding.Models of morphology

There are three principal approaches to morphology, which each try to capture the distinctions above in different ways. These are,- Morpheme-based morphology, which makes use of an Item-and-Arrangement approach.

- Lexeme-based morphology, which normally makes use of an Item-and-Process approach.

- Word-based morphology, which normally makes use of a Word-and-Paradigm approach.

Morpheme-based morphology

In morpheme-based morphology, word-forms are analyzed as sequences of morphemes. A morpheme is defined as the minimal meaningful unit of a language. In a word like independently, we say that the morphemes are in-, depend, -ent, and ly; depend is the root and the other morphemes are, in this case, derivational affixes.[1] In a word like dogs, we say that dog is the root, and that -s is an inflectional morpheme. This way of analyzing word-forms as if they were made of morphemes put after each other like beads on a string, is called Item-and-Arrangement.The morpheme-based approach is the first one that beginners to morphology usually think of, and which laymen tend to find the most obvious. This is so to such an extent that very often beginners think that morphemes are an inevitable, fundamental notion of morphology, and many five-minute explanations of morphology are, in fact, five-minute explanations of morpheme-based morphology. This is, however, not so. The fundamental idea of morphology is that the words of a language are related to each other by different kinds of rules. Analyzing words as sequences of morphemes is a way of describing these relations, but is not the only way. In actual academic linguistics, morpheme-based morphology certainly has many adherents, but is by no means the dominant approach.

Applying a strictly morpheme-based model quickly leads to complications when one tries to analyze many forms of allomorphy. For example, the word dogs is easily broken into the root dog and the plural morpheme -s. The same analysis is straightforward for oxen, assuming the stem ox and a suppletive plural morpheme -en. How then would the same analysis "split up" the word geese into a root and a plural morpheme? In the same manner, how to split sheep?

Theorists wishing to maintain a strict morpheme-based approach often preserve the idea in cases like these by saying that geese is goose followed by a null morpheme (a morpheme that has no phonological content), and that the vowel change in the stem is a morphophonological rule. Also, morpheme-based analyses commonly posit null morphemes even in the absence of any allomorphy. For example, if the plural noun dogs is analyzed as a root dog followed by a plural morpheme -s, then one might analyze the singular dog as the root dog followed by a null morpheme for the singular.

Lexeme-based morphology

Lexeme-based morphology is (usually) an Item-and-Process approach. Instead of analyzing a word-form as a set of morphemes arranged in sequence, a word-form is said to be the result of applying rules that alter a word-form or stem in order to produce a new one. An inflectional rule takes a stem, changes it as is required by the rule, and outputs a word-form; a derivational rule takes a stem, changes it as per its own requirements, and outputs a derived stem; a compounding rule takes word-forms, and similarly outputs a compound stem.The Item-and-Process approach bypasses the difficulties inherent in the Item-and-Arrangement approaches. Faced with a plural like geese, one is not required to assume a null morpheme: while the plural of dog is formed by affixing -s, the plural of goose is formed simply by altering the vowel in the stem.

Word-based morphology

Word-based morphology is a (usually) Word-and-Paradigm approach. This theory takes paradigms as a central notion. Instead of stating rules to combine morphemes into word-forms, or to generate word-forms from stems, word-based morphology states generalizations that hold between the forms of inflectional paradigms. The major point behind this approach is that many such generalizations are hard to state with either of the other approaches. The examples are usually drawn from fusional languages, where a given "piece" of a word, which a morpheme-based theory would call an inflectional morpheme, corresponds to a combination of grammatical categories, for example, "third person plural." Morpheme-based theories usually have no problems with this situation, since one just says that a given morpheme has two categories. Item-and-Process theories, on the other hand, often break down in cases like these, because they all too often assume that there will be two separate rules here, one for third person, and the other for plural, but the distinction between them turns out to be artificial. Word-and-Paradigm approaches treat these as whole words that are related to each other by analogical rules. Words can be categorized based on the pattern they fit into. This applies both to existing words and to new ones. Application of a pattern different than the one that has been used historically can give rise to a new word, such as older replacing elder (where older follows the normal pattern of adjectival superlatives) and cows replacing kine (where cows fits the regular pattern of plural formation). While a Word-and-Paradigm approach can explain this easily, other approaches have difficulty with phenomena such as this.Morphological typology

- For more information, see: Morphological typology.

In the 19th century, philologists devised a now classic classification of languages according to their morphology. According to this typology, some languages are isolating, and have little to no morphology; others are agglutinative, and their words tend to have lots of easily-separable morphemes; while others yet are fusional, because their inflectional morphemes are said to be "fused" together. The classic example of an isolating language is Chinese; the classic example of an agglutinative language is Turkish; both Latin and Greek are classic examples of fusional languages.

Considering the variability of the world's languages, it becomes clear that this classification is not at all clear-cut, and many languages do not neatly fit any one of these types. However, examined against the light of the three general models of morphology described above, it is also clear that the classification is very much biased towards a morpheme-based conception of morphology. It makes direct use of the notion of morpheme in the definition of agglutinative and fusional languages. It describes the latter as having separate morphemes "fused" together (which often does correspond to the history of the language, but not to its synchronic reality).

The three models of morphology stem from attempts to analyze languages that more or less match different categories in this typology. The Item-and-Arrangement approach fits very naturally with agglutinative languages; while the Item-and-Process and Word-and-Paradigm approaches usually address fusional languages.

The reader should also note that the classical typology also mostly applies to inflectional morphology. There is very little fusion going on with word-formation. Languages may be classified as synthetic or analytic in their word formation, depending on the preferred way of expressing notions that are not inflectional: either by using word-formation (synthetic), or by using syntactic phrases (analytic) Read More..

Sounds

As you know, the English alphabet is far from being a regular and consistent system of representing all the sounds in English. For instance, think of the letter group ough. How many different way can it sound like

| Word | Rhymes with.. (in Standard American Dialect) |

| through | true |

| though | go |

| cough | off |

| thought | not |

| tough | stuff |

Unfortunately concensus is the last thing linguists have between them and consequently several systems exist. The most famous one is the International Phonetic Alphabet or IPA, but the American Phonetic Alphabet is also quite widespread. I have chosen to adhere to the American system in this page because that's what I've been taught in. If you are familiar with the IPA there shouldn't really be any problems once you understand corresponding equivalent symbols in the two systems

The following are some of the signs of the American phonetic system. When used for transcription, sounds are put inside square brackets, ie [ ]. Related and similar sounds in a language often occur in complementary distribution, that is, each of these sounds appear only in unique situations. For example, in English, the "t" in "top" sounds different from that in "stop". However, the "t"-sound in "stop" (which is less powerful the the "t" in the beginning of a word) only occurs after a "s" sound, while the "t" in "top" occurs everywhere else, and therefore these two sounds are in complementary distribution. We call this set of sounds a phoneme, and write it between two slashes, ie / /

Formally, /t/ becomes [t] after [s], and becomes [th] everywhere else. The superscript h means that the consonant before it is produced with a little more air

Consonants

Some important points

- V+ denoted "voiced", and V- is "voiceless". Voiceless and voiced simply mean that whether the vocal cords vibrate while making a sound. If you put your hand on your throat and alternate between saying "cod" and "god", you'll notice that "god" makes your vocal cord (or larynx) vibrates more. This is called voiced

- [p], [t], and [k] are unaspirated. For people who know Spanish well, they correspond to the sounds in 'pelo', 'té', and 'cosa'. Such sounds do not occur alone in English, but mostly after the consonant [s], such as in 'space'. Compare 'space' and 'pace', and you'll notice how the /p/ in 'pace' is stronger

- As just mentioned, the sounds /p/, /t/, and /k/ in English occuring at the beginning of the word is aspirated, meaning that more air is pushed out. In Linguistics they are transcribed as [ph], [th], and [kh]. You may think that is impossible to have aspirated /b/, /t/, and /g/, but Proto-Indo-European and Indic languages have them (like in the name of the great Indian epic Mahabharata)

- The columns on the chart refer to points of articulation, that is, places in your mouth where sounds are produced. Bilabial means both of your lips come together, and the sound comes out there (you can feel the vibration between your lips if you try). Labio-dental between your upper lip touches your lower teeth. Inter-dental sounds are relatively rare in the world, and what you do is put your tongue between your two rows of teeth

- Apico-alveolar means putting the tip of your blade right behind your upper row of teeth. Apico-palatal sounds are also called Retroflex. They are pronounced like the Apico-aveolar except with your tongue curled back a little. The most common example for an American English speaker is the 'r' in "road". Retroflex /d/ and /t/ occur in Indian languages (both Indo-European and Dravidian)

- Lamino-palatals are very much like apico-palatals but instead having the tip of your tongue as the highest point the blade, the part behind the tip, almost touches the roof of your mouth

- Dorso-velar, or just velar, sounds are produced between the back of your tongue and the back of your palate. Its cousin, Uvular makes your uvula vibrates, like Parisian French /r/

- Glottal simply means your larynx

- The categories that form the bold rows refer to the type of articulation. Stops are sounds that are maintained for a very short amount of time. You can't stretch no matter how hard you try. On the other hand, Fricatives can persists for forever. Compare between /t/ and /s/

- Sometimes you can merge stops and fricatives to get Affricates, which starts as a stop and turns into a fricative. The /ch/ in English "church" is just an example of an affricate. It starts as a /t/, and turns into a /sh/ sound

- Nasals are, well, nasal. They make your sinus vibrates

- I have no idea why Liquids are called liquids. The voiced apico-palatal liquid /r/ occurs in American English "red" and the voiced apico-alveolar liquid /l/ is like in English "lock", not "table"

- The flap is the Spanish short /r/, ie in "toro". Also occurs in Italian, Japanese, and American English in the form of the /dd/ in "ladder" or /tt/ in "butter" said rapidly

- Semi-vowels are really vowels that appear as the less-powerful part of a diphthong. In other words, they are non-syllabic vowels

Even though they look like English, don't be tempted to pronounce the symbols as if they were English letters. For instance, the symbol [i] really sounds like the 'ee' in "reed". The symbol [e] doesn't sound like the 'e' in 'be', but more like French 'être'

When you say a vowel, you unconsciously change your tongue and lip into an unique configuration characterized by three attributes

- Unrounded vs rounded. This feature applies to your lip. If you say [u] as like "room", you'll notice that your lips forming a circle and you look like you're about to kiss someone. On the other hand, if you say [i] as in "feet" your lips are straight. That's why before you take a picture in America you will tell the people you're about to capture on film to say "cheese", because [i] makes the lips look like smiling

- High to low. You probably never noticed this, but when you say a vowel part of your tongue will raise toward the roof of your mouth while other parts will stay near the bottom. The height of your tongue's peak determines the vowel you say. The sound [i] like in "feet" forces your tongue higher up than, say, the sound [a] as in "father"

- Front, central, and back. This same peak that I just described above can also change in position in your mouth. When the peak is closest to your teeth, it is in front. Toward the throat is back. Between the two is, obviously, central. With [i], the peak of the tongue is a little bit behind your teeth, while with [u] the peak of the tongue is at the back of your mouth, near where the hard palate changes to the soft palate. If you can't picture it, try feeling around with your finger

- Vowels can be long or short. A long vowel is denoted by a colon (:) after the vowel. The best example in English of long vs short can be found in cases like "sad" (long) and "sat" (short). Notice how the 'a' (phonetically [æ]) sounds longer in "sad" than in "sat". So, "sad" is transcribed as [sæ:d] while "sat" is [sæt]

In many languages of the world, tone plays an important role in distinguishing one morpheme from another

Notice that tone isn't the same as stress or intonation. All of these involve changes in the pitch of the voice. Stress, sometimes also known as accent, is the rise and fall of the pitch throughout the syllables of a word. In English, there is usally a highest stress in a word, like "kéyboard" or "exáct", but also in some cases two stresses, one higher than the other, occur, like "singularity". Intonation is the rise and fall of the pitch throughout the words of a sentence. Notice how the statement "You are sick" sounds different from the question "You are sick?" In the statement, the words have more or less even pitches with respect to each other. On the other hand, the question's pitch peaks at the adjective "sick". Both contrasts with an interjection like "You are sick!", which places highest pitches on "You" and "sick"

Tone is somewhat like stress in that it also is the rise and fall of the pitch throughout a word. However, tone is used to distinguish words that have the same sounds which may have unrelated meanings, while stress is not. (Actually, in a few cases, stress does serve to distinguish different meanings or version of the same word, but never consistently as tone.

Furthermore, the beginning pitch and the ending pitch of a tone is central to distinguishing words. Slightly different beginning or ending pitch means different words. On the other hand, the highest point in a stress can be any degree of pitch above the unstressed syllables. The difference doesn't matter as long as the stress rises above the other syllables

There are several ways of representing tones in Romanization. Pinyin (for transcribing Mandarin) and Vietnamese uses diacritics. Some phonetic transcriptions use single digit numbers. So 1 in Cantonese is the high falling tone, 2 is the low falling tone, and so on. Neither system directly indicates the tone

There are two other systems that do directly illustrate the tonal change. One uses a vertical bar to denote a scale, and horizontal or diagonal lines to represent the change in pitch

The best system that I have seen is a two digit number, ranging from 1 to 5. The first (leftmost) digit is the starting pitch, and the second (rightmost) digit is the ending pitch. Together, it tells you which pitch to start and which to end

Since I am a native speaker of Cantonese, I'll use its tonal system for demonstration. In traditional Cantonese, there are 9 basic tones, but in my dialect (Hong Kong) the high rising and low rising tones have become indistinguishable. Also, the high falling tone has become very similar to the high-level tone (which doesn't technically exist in Cantonese but can be found in Mandarin). I will try to reproduce all the distinguishing details in these tones, but don't take my pronunciation as canonical. The rest are relatively close to reality

| Description | Example | Sounds |

| High falling | [ma53] "mother" | AU | WAV |

| Low falling | [ma31] "sesame; hemp" | AU | WAV |

| High rising | [ma35] ??? | AU | WAV |

| Low rising | [ma13] "horse" | AU | WAV |

| Mid level | [ma33] "question marker" | AU | WAV |

| Low level | [ma11] "to scold" | AU | WAV |

| High short | [pok55] "to hit" (quite onomatopeic) | AU | WAV |

| Mid short | [pok44] "to struggle (restlessly)" | AU | WAV |

| Low short | [pok22] "thin" | AU | WAV |

Indo-European

The most well known of all language families is the Indo-European, which comprises roughly 12 major groups and hundreds of languages. The major groups or subfamilies are Celtic, Italic (including Romance), Baltic, Slavic, Germanic, Anatolian, Greek, Indic, Iranian, Tocharian, Albanian, and Armenian. In addition, it appears that Baltic and Slavic should form a larger Balto-Slavic group, and Indic and Iranian should be placed in an Indo-Iranian group.

Here's small list of words common to most Indo-European languages:

| Group | Language | | ||||||

| "father" | "mother" | "brother" | "two" | "three" | "four" | "horse" | ||

| Germanic | Old English | fæder | modor | broðor | twa | thrie | feowre | eoh |

| Italic | Latin | pater | mater | frater | duos | tres | quattuor | equus |

| Celtic | Old Irish | athair | mathair | brathir | do | tri | ceathair | ech |

| Hellenic | Greek | pater | meter | phrater 1 | duos | tri | tetra | hippos |

| Indic | Sanskrit | pitar | matar | bhratar | dva | trayas | chatvari | asva |

| Iranian | Avestan | pitar | matar | bratar | dwa | trayo | chatvaro | aspa |

| Slavic | Russian | otech | matka | brat | dva | tri | chetyre | loshaa (kon) |

| Armenian | Armenian | hayr | erku | erek' | cork' | |||

| Tocharian | Tocharian B | pacer | macer | procer | wi | trai | s'twer | yakwe |

| Proto-Indo-European | *pəter | *mater | *bhrater | *duwos | *treyes | *kwetores | *ek'wos | |

1. Greek phrater means "clan member"

Sino-Tibetan

Another large language family is the Sino-Tibetan, including Sinitic (all forms of Chinese) on one main branch and Tibeto-Burman (Tibetan, Burmese, and thousands of others) on the other main branch.

In the following example tones are omitted so that I have less work to do :) Also, note that I threw out Pinyin transliteration for Mandarin and used something of my own that also works for other dialects: /ś/ corresponds to voiceless palatal fricative (/x/ in Pinyin) much like /ch/ in German ich; /x/ is the voiceless velar fricative like /ch/ in Scottish loch; /ə/ is the central vowel schwa; /ʔ/ is the glottal stop; and /C/ means any stop consonant.

| Group | Language | | ||||||

| "I", "me" | "two" | "three" | "six" | "name" | "eye" | "blood" | ||

| Sinitic | Mandarin | wo | er | san | liu | ming | mu | śie |

| Sinitic | Yue | ngo | yi | saam | luk | ming | muk | hüt |

| Sinitic | Wu | ngu | liã | se | loʔ | ming | moʔ | śiʔ |

| Sinitic | Middle Chinese | nguo | ñi | sam | lyuk | myeng | muk | xwiet |

| Sinitic | Old Chinese | nguo | niys | səm | C-ruk | myeng | myək | swi:t |

| TB | Tibetan | nga | gñis | gsum | drug | ming | myak | yi (1) |

| TB | Burmese | nga | hnats | sum | khrok | ə-mañ | mig | swiyh |

| TB | Kachin | ngai | ñi | məsum | kruʔ | mying | myiʔ | sai |

| TB | Lepcha | ka | nyi | sam | ta-rak | ming | mik | vi |

Why do languages change? Well, there's been many theories about why languages change. This has intrigued people since time immemorial and it seems that almost everybody has an idea. One early example can be found in Bible in the form of the Tower of Babel, where God decided humans got a little too much hubris (oops...wrong mythology) and so made their lives miserable by giving everybody different languages.

As science became a more dominant force in society, scientific explanations to language change were proposed. Here's a few through the years:

Language Decay?

The 18th century view of language is one of decay and decadence. Their reasoning is that the old Indo-European languages like Sanskrit, Greek and Latin all have complex declension and conjugation schemes, where as the modern Indo-European languages have far fewer cases for declension and conjugation. This "loss" of declension and conjugation cases was a result of speakers of the language getting increasingly careless about their speech (read "lazy"), so the modern speakers are "decadent" as they have allowed the once complex language to decay into such a "simple" language.

Obviously, this "decadence" argument has one major flaw. Even though the number of declensions and conjugations has dwindled, other parts of speech such as particles and auxiliary verbs have evolved to take their place. Anything that can be expressed in the ancient tongue can still be expressed today. Ultimately, this theory is highly subjective, as it relies on personal opinions, not scientific facts, of what is "highly evolved" and what is "decadent". Therefore this is not science.

Side note here: Even though linguistics has moved beyond this 18th century theory of language decay, many self-appointed pundits are still using this excuse to stamp out dialectal variations throughout the world by justifying the dialects as "decadent". This is, of course, complete nonsense, as even the most weird sounding dialect has regular grammatical structure and works perfectly to express ideas as well as the standard language.

Natural Law?

The next theory, proposed by the Neogrammarians (Junggrammatiker) in the late 19th century, is one of natural process. The Neogrammarians stated that changes are automatic and mechanical, and therefore cannot be observed or controlled by the speakers of the language. They found that what sounds like a single "sound" to a human ear is actually a collection of very similar sounds. They call these similar sounds "low-level deviation" from an "idealized form". They argue that language change is simply a slow shift of the "idealized form" by small deviations.

The obvious problem here is that without some kind of reinforcement, the deviation might go back and forth and cancel out any change. Then the Neogrammarians patched this theory by adding reasons for reinforcing the deviation such as simplification of sounds, or children imperfectly learning the speech of their parents.

The simplification of sounds basically states that certain sounds are easier to pronounce than others, so the natural tendency of the speakers is to modify the hard-to-say sounds to easier ones. An example of this would be the proto-Romance word /camera/ "room" changing into early French /camra/. It is hard to say /m/ and /r/ one after another, so it was "simplified" by adding /b/ in between, to /cambra/ (hence leading to modern French "chambre"). A more recent example is the English word "nuclear", which many people pronounce as "nucular". The problem with this patch is that since not everything in a language is hard-to-pronounce (unless you're speaking Klingon), the process would only work for a small part of the language, and could not be responsible for a majority of sounds changes. Secondly, it is highly questionable to determine whether "nucular" or "nuclear" is easier to pronounce. You'll get different answers from different people. Simplification no doubt exists, but using it as a reason (not a symptom) of language change is too subjective to be scientific.

The next patch, that of children incorrectly learning the language of their parents, doesn't work either. Let's take an extreme case in the form of immigrants. What is observed is that children of immigrants almost always learn the language of their friends at school regardless of the parents' dialect or original language. (And yes, the children become multilingual, but that's another story...) In fact, children of British immigrants in the United States nearly always speak with one of the many regional American accents. So in this case, the parents' linguistic contribution becomes less important than the social group the child is in. Which leads to...

It's Social Bonding

The last theory advanced during this century is a social one, advocated by the American linguist William Labov. What he found was that at the beginning a small part of a population pronounces certain words that have, for example, the same vowel, differently than the rest of the population. This occurs naturally since humans don't all reproduce exactly the same sounds. However, at some later point in time, for some reason this difference in pronunciation starts to become a signal for social and cultural identity. Others of the population who wish to be identified with the group either consciously or (more likely) unknowingly adopt this difference, exaggerate it, and apply it to change the pronunciation of other words. If given enough time, the change ends up affecting all words that possess the same vowel, and so that this becomes a regular linguistic sound change.

We can argue that similar phenomena apply to the grammar and to the lexicon of languages. An interesting example is that of computer-related words creeping into standard American language, like "bug", "crash", "net", "email", etc. This would conform to the theory in that these words originally were used by a small group (i.e. computer scientists), but with the boom in the Internet everybody wants to become technology-savvy. And so these computer science words start to filter into the mainstream language. We are currently at the exaggeration phase, where people are coining weird terms like "cyberpad" and "dotcom" which not only drive me crazy but also didn't exist before in computer science.

To me the social theory of language change sounds much more plausible than other previous theories. Humans are, after all, social animals, and rarely we do things without a social factor.

What ancient scripts ultimately capture is part or whole of a tongue spoken in antiquity. However, as you may have noticed, all human languages evolve over time. For instance, English poems written in Shakespeare's time don't rhyme correctly anymore, but a look at their archaic spelling indicates that they should rhyme.

As changes accrue over time, ancient texts become unintelligible if the knowledge of the language is lost. In some cases, the texts can be read, but cannot be understood. The best example of this is Etruscan, which is written in a script nearly identical to the Roman alphabet, so individual sounds and words can be isolated. However, since nobody knows what the words' meanings and the grammatical rules of Etruscan, the texts remain relatively obscure.

Alas, not all is lost. If ancient language had survived and evolved into later, "daughter", languages that can be understood, then it becomes possible to know something the "parent" language as well as the processes involved in the evolution. This study of language change through time is called historical linguistics.

The State of US Teachers

-We will need over 2 million new teachers in the next 10 years. -Twenty percent of teachers quit within the first 3 years of their teaching careers. -33 percent of teachers quite within the first 5 years of their teaching careers. -The main reason teachers quit is because they feel they are not making enough money. Starting teachers can make as little as $20 000 per year, barely above the poverty line. -Other reasons to quit include: misbehaved students, disrespectful students, whining parents, angry parents, growing families, desire for change, and long hours in the classroom. Teachers feel that their profession is not fully appreciated or understood. Many will meet highschool friends and be laughed at when they tell them what their job is. -Teachers find it difficult to cope with the wide range of students in every classroom- different races, religions, and financial levels. -Students want to be teachers because they feel they can positively affect a child’s life and because they excel in a certain subject. They like being able to help their own communities. -Many of our long-lasting teachers were inspired by past teachers and other role models in the education system. -One top teacher wanted to be a movie-star, a missionary, and a mechanic as a child. She feels that as a teacher she can be all three of these things. -A teacher that does not have set expectations of her students or strong inner will power will likely leave the profession quickly. -Teachers are very stressed and they lose sleep and personal downtime because they worry about their students and they have so much marking to do. -Teachers generally think poorly of themselves and consider the jobs they do to be of a low quality. This is because they are so hurried in the day that they simply can’t do all the things that they want to do. -Teachers have to realize that they don’t have the power to make a student succeed and that, although they can try, they cannot make a student hand in an assignment. -The best teachers are the ones who can find something about every student that is good and love and appreciate each one equally. -The best teachers realize that teaching involves more than covering the curriculum with students . It involves counseling them about their futures. Many children really don’t know what to do in life and the teacher is the person who will put them on the right path

A look at the schools in Edmonton Alberta

Alberta has a unique and appealing school system that is worth looking into. It has a variety of schools that cater to special groups. The public school system was losing a lot of students before it came up with its new program.

Some of the new schools they have designed are already in place elsewhere in Canada, but never in the public school system. One of their hits is a native school, where students of native ancestry are not so likely to lose their heritage. They begin each day with the burning of incense and a sort of prayer. Another hit is the all-girls middle school. At a difficult time in their development, the girls do not have to worry about dressing up and looking pretty for their beau. Instead they can focus on their education. This is an exciting opportunity that many parents are taking advantage of.

Other schools include a military school for highschool aged boys. This school teaches them such things as military heritage. There is a kindergarten to grade 12 arts school for parents who want their children to have more exposure to the arts rather than the sciences. Of course, the majority of schools are just your typical public schools, but everyone has the option of attending the specialized schools if they wish.

After these new schools opened, the enrolment rate in the public school system skyrocketed. And why not? If a parent is paying big dollars for their child to attend a private school, and then the public schools offer the same sort of program free of charge, why not take advantage of it! It is a win-win situation. And the children are more eager to learn if they are in a program that interests them.

Perhaps this is the way to go for the rest of Canada. Obviously, by catering to the needs of individuals, you can satisfy an entire group of students. Some may argue, however, that this is not Canada. Everyone is equal and we should all bring our differences together into the same classroom. This is a nice idea but it just doesn’t work in the classroom. Students are frequently racist and inconsiderate when given the chance to be. If they are segregated into interests groups, perhaps they will be better able to see the similarities between each other. For example, all the students in the arts school will share a common interest in art whether they are Muslim and black or Catholic and white.

Teachers in the Special Education Field

Special education, says James Kaufmann, has ten problems today. It is considered to be: (a) ignorant of history, (b) apologetic for existing, (c) preoccupied with image, (d) lost in space, (e) unrealistic in expectations, (f) unprepared to focus on teaching and learning, (g) unaware of sociopolitical drift, h) mesmerized by postmodernist/deconstructionist inanities, (i) an easy target for scam artists, and (j) immobilized by anticipation of systemic transformation. James M. Kauffman, Commentary: Today's Special Education and Its Messages for Tomorrow. Vol. 32 no, Journal of Special Education, 01-15-1999.

James Kauffman writes for the Journal of Special Education, and he most definitely has a true trend here. Special education is a diminishing program, at least it is in Ontario. The constant government cuts to education have saw its budget being slashed in every area, resulting in a system with more troubles than the students it serves.

Special education used to involved small remedial classes with extensive help for troubled students. My daughter once attended a session because her Rs sounded like Ws. Now, however, these classes are a part of history. Students who are behind or in need of extra help are simply sent to the basement, where one, or at most two special ed teachers serve a school of 700 people. It is rather daunting.

This new program is not just hurting the students who need extra help, nor just the teachers who have lost their jobs; it is hurting the entire system of education. Stronger students must wait in boredom as classroom teachers spend significant amounts of time with the struggling students. Less material can be taught and students fall behind their peers at other schools.

Obviously Kauffman’s ten points are the result of a lack of funding. It is extremely difficult to correct any of there things if the money isn’t there. Teachers need to speak to their boards, talk to the trustees, and even send letters to education officials. We need to let our governments see how much our special education systems are suffering as a result of their funding cuts. Obviously a poorly funded education system can not provide students with a rich and sufficient education. It should be part of a teacher’s goal to reverse these funding cuts. Until then, teachers must do as much as they can for their struggling students, including giving them extra help even after school and during lunch break. In this way, students will not become disillusioned and behind.